This history is kept alive no matter how sad it is, no matter how much injustice and tragedy it carries. We keep it alive because if we forget this story, we forget part of our identity. This history not only has made us sad, it’s made us strong, it’s made us resilient.

sisa-wipam (Roberta Conner)

As we neared the end of our September visit to the Pioneer Mountains in Southwest Montana, smoke from the historic 2020 wildfires continued to direct our adventures. Air quality was so poor that officials advised people to stay indoors—not exactly the healthiest conditions for hiking at high elevation. On our final day exploring the area, we set our hiking boots aside and focused on our quest to see all 422 National Park Units. Today’s adventure took us to the only National Battlefield west of the Mississippi, Big Hole National Battlefield.

On August 9, 1877 gun shots shattered the peace of a sleeping camp of Nez Perce Indians camped along the banks of the North Fork Big Hole River. After two days of battle, 60 – 90 Nez Perce men, women, and children were dead along with 31 soldiers and volunteers. Big Hole National Battlefield was created to honor all who were there. It is also part of the larger Nez Perce National Historical Park which consists of 38 sites in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Combined, these two National Park Units tell the story of the nimí·pu (Nez Perce) and the Flight of 1877.

Since time immemorial, the river gorges, valleys, mountains, and prairies of the Inland Northwest have been home to the nimí·pu (Nez Perce). It was the Nez Perce who befriended the Lewis and Clark Expedition as they emerged, nearly starved to death, from the Bitterroot Mountains onto the Weippe Prairie in September 1805. During the early settling of the Northwest, they maintained a reputation as a people of peace. By the 1860s, encroaching white settlements and the discovery of gold changed everything.

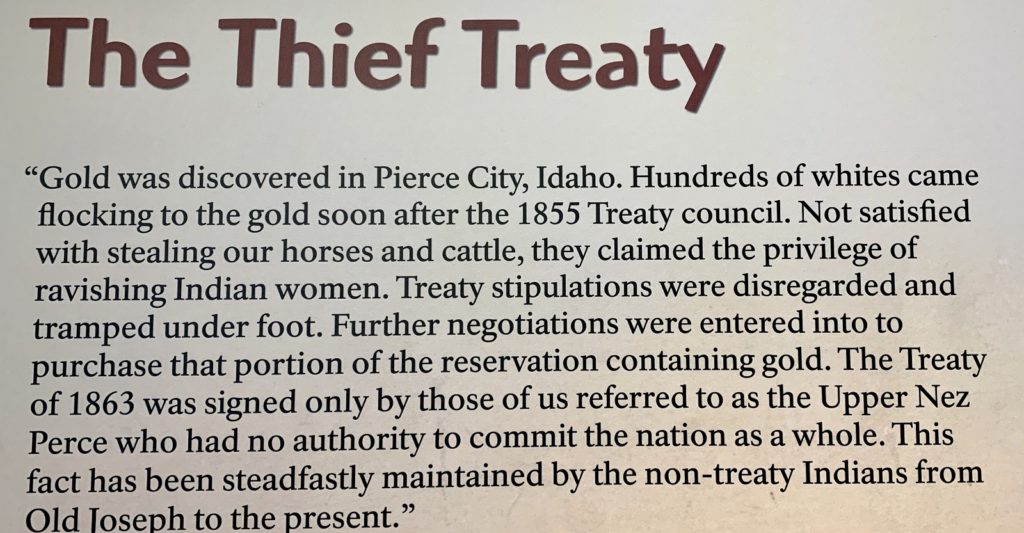

In 1855, territorial governor Isaac I. Stevens met with the Umatilla, Yakama, Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Palouse tribes. The Nez Perce agreed to cede 7.5 million acres of tribal land while still retaining the right to hunt and fish in their “usual and accustomed places”. In just five short years, gold was discovered on the reservation. Rather than stop whites from trespassing on reservation land, the U.S. government forced the 1863 Treaty which shrank the 1855 reservation by 90% and robbed the Nez Perce of another five million acres. The bands that lived outside of the new boundaries, including Chief Joseph’s Wallowa band, refused to accept the new terms; however, 51 headmen who lived within the proposed reservation boundaries signed the new treaty. The 1863 Treaty became known as the ‘Thief Treaty’ and it deeply divided the nimí·pu. It also created conditions that would eventually lead to an armed clash between the Nez Perce and the US Army, now known as the Nez Perce Flight of 1877.

In June 1877, 600 Nez Perce from several non-treaty bands gathered at Tolo Lake near current day Grangeville, Idaho. Even though they had not signed the Thief Treaty, they were complying with the U.S. government’s demand to leave their traditional homelands and resettle on the reservation near Lapwai. As someone who has spent nearly their entire life on the ancestral lands of the Nez Perce, I cannot imagine being forced to give up my home in the stunningly beautiful Wallowa Valley and my way of life. On the night of June 13, three young warriors, angered by past murders of warriors and raping of women by white settlers, left the encampment in search of Larry Ott, who had killed one of their fathers. Unable to find Ott, they raided other settlements. Several more warriors joined and within two days 15 settlers had been slain in the Salmon River Country.

You might as well expect the rivers to run backwards as that any man who was born a free man should be contented penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases. I have asked some of the great white chiefs where they get their authority to say to the Indian that he shall stay in one place, while he sees white men going where they please. They cannot tell me.

hinmato-wyalahtqit (Young Joseph)

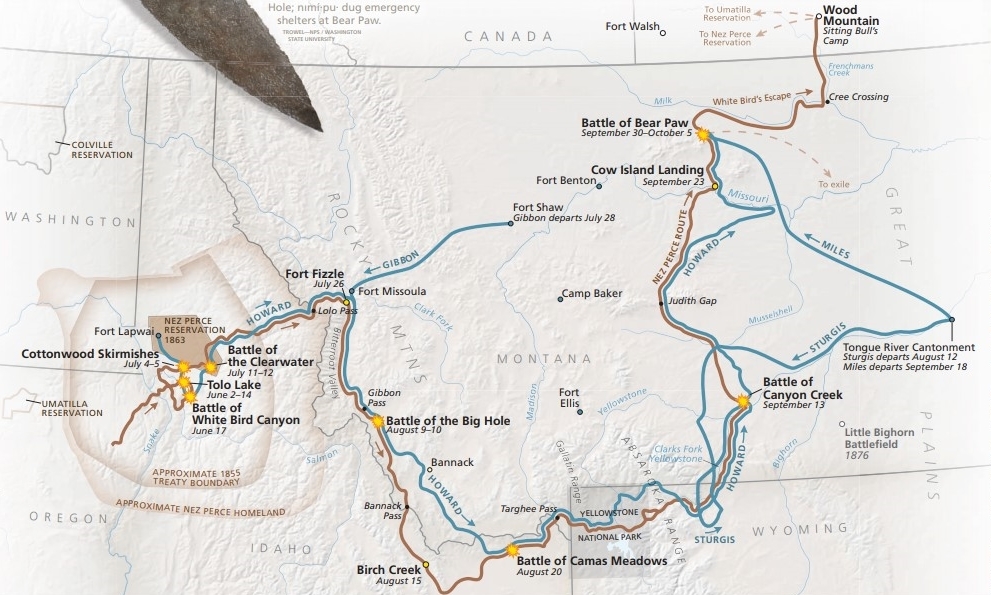

Fearing U.S. Army retaliation, Joseph decided that the best way to avoid the U.S. Government policy of forcing Native Americans onto reservations was to escape to Canada, where he believed that his people would be treated fairly and they could unite with Sitting Bull, leader of a band of Lakota there. Thus began a 126-day journey that spanned over 1,170 miles through Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Multiple battles were fought along the way as U.S. forces pursued the Nez Perce who were trying to peacefully escape. At White Bird Canyon in Idaho, U.S. forces were defeated after firing on the Nez Perce who came in under a white flag.

By early August 1877, 800 Nez Perce and 2,000 horses were passing peacefully through the Bitterroot Valley in Western Montana. The leaders believed the military would not pursue them into Montana. When the Nez Perce arrived at Big Hole on August 7th, they did not know forces were close behind them. On the morning of August 9, U.S. troops surprised the sleeping Nez Perce with a dawn attack. The Nez Perce mounted a fierce resistance and managed to overwhelm the attacking force. The Nez Perce lost an estimated 60 to 90 men, women and children, while U.S. forces lost 31. The confrontation was the most violent battle of the conflict.

Everybody was sleeping when the soldiers charged. They set fire to a few tepees. Little children were in some of those tepees…We found the bodies all burned and naked.

ewyi-n (Wounded)

Additional battles were fought at Camas Meadows, Canyon Creek, and Bear Pass as the Nez Perce fled through Yellowstone National Park on their flight to Canada. In October 1877, just 40 miles from the Canadian border, the starving and exhausted Nez Perce surrendered to General Olive Howard, after he said they would be allowed to return to the Wallowa Valley—that was a lie. Approximately 450 were taken captive and sent as prisoners of war to Kansas and Oklahoma. Others evaded capture and secretly returned to familiar places near home or sought refuge among other tribes and in Canada.

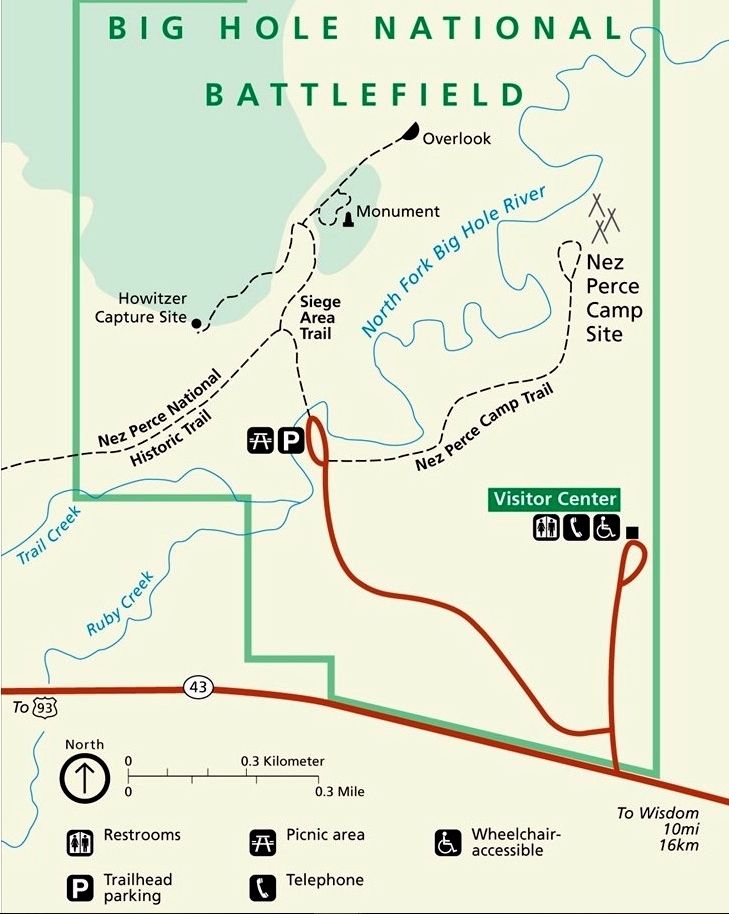

Big Hole National Battlefield is located ten miles west of Wisdom, Montana on Highway 43. For you National Park Unit junkies (like me), two National Historic Trails cross here as well—Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail and Nez Perce National Historic Trail. The park is open every day of the year except Veteran’s Day and Thanksgiving. Admission is free. I recommend allowing half a day for your visit. Check out the exhibits, film, and observation deck at the visitor center. Take in a ranger program and definitely walk at least one of the battlefield trails and imagine what those two terrible days were like for both sides.

During our visit, we made a quick pass through the visitor center which was open, but under COVID precautions. We hiked all three of the battlefield trails that are accessed from the lower parking lot. We started with the 1.6 mile round-trip Nez Perce Camp Trail which was an easy hike to the site where the sleeping Nez Perce were camped when the army attacked on the morning of August 9, 1877. From there we followed the 1.2 mile round-trip Siege Area Trail that climbed to the rifle pits dug by the soldiers. Nez Perce warriors besieged the troops here after pushing them out of camp. We ended with the Howitzer Trail which is a moderately steep 0.8 mile spur trail off the Siege Trail. At the top, a replica cannon marks the spot where Nez Perce warriors captured a mountain howitzer cannon.

Respecting Sacred Ground

Big Hole Battlefield is sacred ground for all who fought here. It remains a burial ground and a place of mourning and remembrance. As you walk around the battlefield, please be respectful to those who died here. Unmarked graves exist here; please stay on trail. Leave all items at tipi memorials in place and undisturbed. These are sacred offerings that nimí·pu leave in memory of their ancestors. Digging in the area or collecting rocks or other items is not allowed. Metal detector and drone use are strictly prohibited throughout the park.

Offerings at Chief Joseph’s tent

Wounded Head’s drinking horn was painted red in memory of his using it to bathe his injured head after being shot at Big Hole. Look closely and you will see the dots he carved into its surface to tally the nimí·pu who died at Big Hole. One of these dots represents his young daughter

As I sit retrospecting so vividly on those distant days when battles took place between your brave ancestors and my fellow soldiers, it is with saddened regret that I, and they, were compelled to carry out the orders of our superior officers, when we knew they were fighting for the preservation of their homes and the right to live their own lives, and their own religious beliefs.

Corporal Charles Loynes at age 90

Related Posts

- Montana’s Pioneer Mountains National Scenic Byway Part 1: Camping & Hiking

- Montana’s Pioneer Mountains National Scenic Byway Part 2: Historical Sites

- Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site & Historic Deer Lodge, Montana

The Adventure Continues

Thanks for joining us on our adventures to Montana’s Pioneer Mountains. Join us for our next post as we head to the backcountry of Idaho for some fall trout fishing. And don’t forget to check out our Amazon RV and Adventure Gear recommendations accessed via links at the top of our home page. We only post products that we use and that meet the Evans Outdoor Adventures seal of approval. By accessing Amazon through our links and making any purchase, you get Amazon’s every day low pricing and they share a little with us. This helps us maintain Evans Outdoor Adventures and is much appreciated!

That was very interesting. Thank you

I enjoyed all the pictures and the narrative. Especially the one with Lusha by the cannon. The background is beautiful!