Beautiful spring hiking along the Hanford Reach and White Bluffs area of the Columbia River complete with desert wildflowers, sand dunes, towering cliffs, a birder’s paradise, and an eerie WWII and Cold War legacy.

Distance: South Slope 7.0 miles and North Slope 6.0 miles (these were our mileages, but these could be shortened or extended to suit most hikers)

Type: out and back

Difficulty: easy with minimal elevation gains

Best season: spring (accessible year around, but oppressively hot in the summer)

A three day weekend over Easter had us searching for hiking destinations with a favorable weather forecast. Desert locations are typically the safest bet for Washington hiking in March and this weekend was no exception. After a week of record setting rains, snow, and hail at home, the weather forecast for the Columbia River Basin sounded perfect—62 degrees and sunny.

Thumbing through our Washington hiking guidebooks, a color photo caught my eye. It showed towering white bluffs along a river with the title “White Bluffs North Slope”. I read the full trail description and it sounded perfect for spring explorations. Nearby White Bluffs South Slope would keep us busy a second day. We were set. Friday morning we drove from our home in Eastern Washington to the White Bluffs South Slope Trailhead. We arrived to an empty parking lot with temperatures around 60 and mostly sunny skies. Perfect!

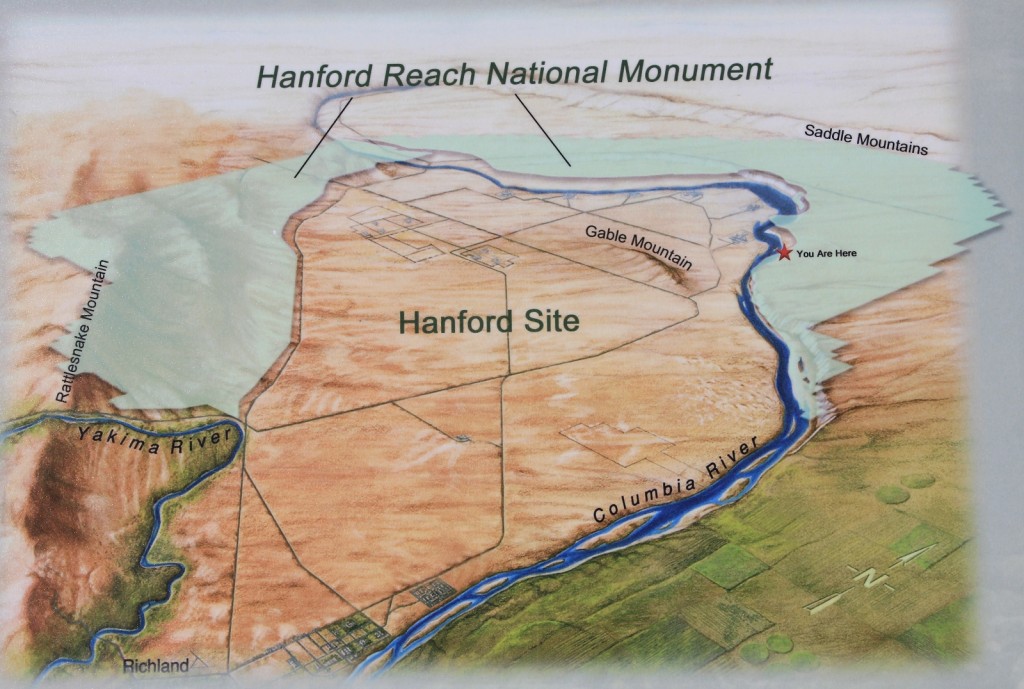

At the trailhead was a nice overlook of the Columbia River. This area is now part of the Hanford Reach National Monument which was set aside by President Clinton in 2000. Most of the monument is carved from the former security buffer surrounding the Hanford Nuclear Reservation which produced the majority of the plutonium found in the U.S. nuclear arsenal (for those interested, see a more thorough history below). The area has been untouched by development or agriculture since 1943 when the government seized the land from locals “for the war effort” and closed it off to public access.

The monument is named after the Hanford Reach, the last non-tidal, free-flowing section of the Columbia River in the United States and one of the Northwest’s best salmon spawning grounds. The area is part of the Columbia River Plateau, formed by basalt lava flows and water erosion. The shrub-steppe landscape is harsh and dry, receiving between 5 and 10 inches of rain per year. Forty-eight rare, threatened, or endangered animal species call the monument home.

After visiting the overlook, we hit the trail. We started by walking around the gate at the end of the road and proceeding a short distance on gravel road. Immediately after rounding the first bend from the parking lot, the gravel road turned to an old paved road.

We quickly realized that the South Slope trail is an old road that has been closed off since 1943 when the US Government condemned and evacuated the towns of Hanford and White Bluffs to make room for Hanford Nuclear Reservation. The road descended roughly 500’ to near the river. We had nice views of the Hanford Reach to the right and interesting bluffs to the left. Across the river, retired nuclear reactors were an eerie reminder of this area’s secret past. We didn’t see any wildlife, but did hear a lot of birds. During the hike we saw one couple, a family of 3, and one very nice older gentleman who was headed out for a little fishing. Other than that, it was a quiet day on the trail.

We walked 3 miles from the northern trailhead, along the paved road, to the southern trailhead (which I didn’t even know existed). At the southern trailhead, we took a long break sprawled out on the green grass, watching the river go by. Before heading back, we did some off trail exploring up on the hillside. We hiked approximately 7 miles roundtrip.

Directions to White Bluff South Slope trailhead: From Othello drive south on highway 24 approximately 16 miles to just before milepost 63. To the right is a sign for White Bluffs Area. Turn left here and pass through a solar powered gate that closes at night. Follow the wide and well maintained gravel road 4.0 miles to a 4-way junction. Continued straight for another 4 miles to the end of the road where an overlook and the trailhead are located. Our trail guide stated we’d need a WA Fish and Wildlife vehicle permit, but we did not see any signs indicating such.

Alternate directions to southern trailhead (we did not go this way, but found these directions on the WTA website): From I-182, take the Road 68 exit from Pasco and head north on Road 68 until it turns into Taylor Flats. Follow Taylor Flats and take a left after the road ends on Ringold Road. Follow it for a few miles until you reach a sign that instructs you to turn left towards Ringold. Once at Ringold follow the gravel road north until you reach a sign that says no automobiles.

Sunday morning, we retraced our drive from the previous day and took the turn for the North Slope TH at the 4-way intersection. The road immediately turned from gravel to what appeared to be brand new pavement. We drove to the end of the road to see the boat launch which is located at the old White Bluffs Landing where a ferry used to cross the river. There was a nice stone marker here stating White Bluffs settlement was established at “a natural crossing on the Columbia River. White Bluffs became an important transportation hub where supplies shipped by steamers from The Dalles, Oregon were loaded onto pack trains destined for mining sites in Northern Idaho, Montana, British Columbia, and Ft. Colville, Washington. In its most prosperous years between 1858-1870, the community included a Wanapum village, ferry, army depot, saloon, trading post, warehouse, and houses. In the early 1900s, most of the town relocated across the river. In 1943, the World War II Hanford Project appropriated the land at this site.”

We drove the short distance back up the hill to the trailhead located at a large clump of cottonwood trees. We were the only car in the parking lot.

It was a cool start to the morning with temperatures in the low 40s and mostly cloudy conditions. The forecast was for 61 and sunny by mid-day, so we knew we’d having improving weather over the hike.

The unmarked but obvious trail immediately climbs a few hundred feet out of the parking lot with nice views of the White Bluffs towering above the river to the north. The hillsides were bright green from all the recent rain and sun. Buttercups were everywhere. The air was alive with bird songs including three chattering kingfishers who were chasing one another. After just a few minutes, we saw a bald eagle perched on the side of the bluffs.

Soon, we topped out and had good views of the Columbia River, including several of the old plutonium reactors across the river. We made our way north 2 miles to a series of large sand dunes. We climbed to the top and followed those out to the last and tallest dune about a mile away. The hiking here was moderately difficult as we made our way through loose sand.

We took a nice break at the top of the tallest sand dune. We had impressive views in all directions. We decided to make this our turn around point as the trail didn’t look to offer much new after that point.

The sun came out for most of our return trip making for much better photographs. After dropping down off the sand dunes, we caught the low trail that we had seen on the way in. It followed the tops of the bluffs more closely making for an interesting return loop. About ½ mile from the TH, we encountered our first people of the day. Back at the TH, we found 5 cars besides ours. One belonged to a nice young couple with a baby in a hiking pack. It was their first time hiking the trail, so exchanged a few tips. We had hiked 6.0 miles round trip.

Directions to White Bluff North Slope trailhead: From Othello drive south on highway 24 approximately 16 miles to just before milepost 63. To the right is a sign for White Bluffs Area. Turn left here and pass through a solar powered gate that closes at night. Follow the wide and well maintained gravel road 4.0 miles to a 4-way junction. Turn right and transition to paved road. Continued straight for another 2 miles to the end of the road where a modern boat launch sits where the old White Bluffs Ferry used to transport passengers across the Columbia. There are outhouses here and a historic old cabin with nice interpretive marker. Return back up the road to the large clump of trees on the left. This is the unsigned trailhead. Our trail guide stated we’d need a WA Fish and Wildlife vehicle permit, but we did not see any signs indicating such.

A summarized history for those who are interested (taken from Wiki)

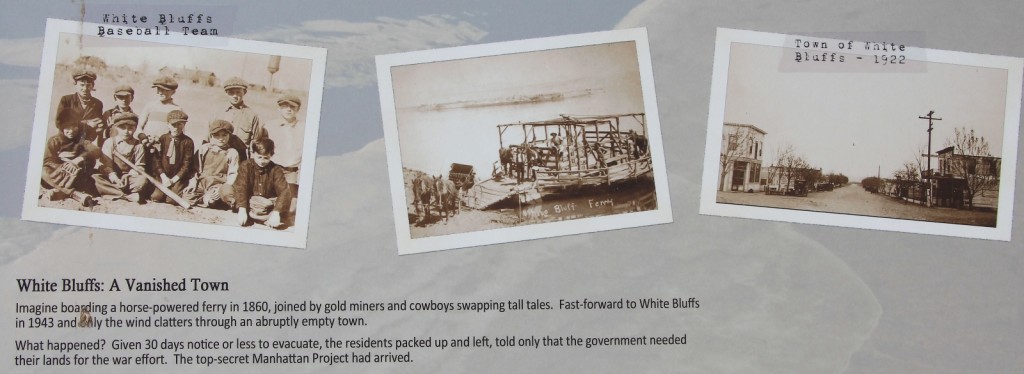

White Bluffs was depopulated in 1943 along with the town of Hanford to make room for the nuclear production facility known as the Hanford Site. Prior to the arrival of white settlers, the land was inhabited by the Wanapum Indians, a tribe closely related to the Palouse,Yakama, and Nez Perce tribes. The first white settlement at White Bluffs was in 1861. The original townsite was located on the east bank of the Columbia River. A ferry was built to accommodate traffic across the Columbia headed for the gold rush in British Columbia. By the early 1890s the population had grown and the town expanded to the west bank of the Columbia in Benton County. When U.S. government seizures of homes of White Bluffs residents occurred beginning in March 1943, some homes were seized immediately for government office buildings. Residents were given from three days to two months to abandon their homes. Homes and orchards were burned by the government to clear the site. The remains of some 177 persons buried at the White Bluffs Cemetery were moved to the East Prosser Cemetery, some 30 miles away. At the time of the government destruction of the town, production of pears, apples, vegetables, and grapes for wine production were primary sources of livelihood. Today, almost nothing remains of the town.

Hanford was a small agricultural community. It was depopulated in 1943 in order to make room for the nuclear production facility known as the Hanford Site. The town was located in what is now the “100F” sector of the site. The original town was settled in 1907 on land bought by the local power and water utility. In 1913, the town had a spur railroad link to the transcontinental Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway. By 1925 the town was booming thanks to high agricultural demand, and it boasted a hotel, bank, and its own elementary and high schools. The town was condemned by the Federal government to make way for the Hanford site. Residents were given a thirty day eviction notice on March 9, 1943. Most buildings were destroyed, with the notable exception of the high school. It was used during WWII as the construction management office.

The Hanford Site is a mostly decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Washington. Established in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project the site was home to the B Reactor, the first full-scale plutonium production reactor in the world. Plutonium manufactured at the site was used in the first nuclear bomb and in Fat Man, the bomb detonated over Nagasaki, Japan.

During the Cold War, the project expanded to include nine nuclear reactors and five large plutonium processing complexes, which produced plutonium for most of the more than 60,000 weapons in the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Government documents have confirmed that Hanford’s operations released significant amounts of radioactive materials into the air and the Columbia River. Decades of manufacturing left behind 53 million gallons of high-level radioactive waste an additional 25 million cubic feet of solid radioactive waste, and 200 square miles of contaminated groundwater beneath the site. In 2007, the Hanford site represented two-thirds of the nation’s high-level radioactive waste by volume. Hanford is currently the most contaminated nuclear site in the United States and is the focus of the nation’s largest environmental cleanup.

The Hanford Site occupies 586 square miles—roughly equivalent to half of the total area of Rhode Island. This land is closed to the general public. The original site was 670 square miles and included buffer areas across the river. Some of this land has been returned to private use and is now covered with orchards and irrigated fields. In 2000, large portions of the site were turned over to the Hanford Reach National Monument.

The archaeological record of Native American habitation of this area stretches back over ten thousand years. Tribes and nations including the Yakama, Nez Perce, and Umatilla used the area for hunting, fishing, and gathering plant foods. Native American use of the area continued into the 20th century, even as the tribes were relocated to reservations. The Wanapum people were never forced onto a reservation, and they lived along the Columbia River until 1943. Euro-Americans began to settle the region in the 1860s, initially along the Columbia River south of Priest Rapids. They established farms and orchards supported by small-scale irrigation projects and railroad transportation, with small town centers at Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland.

During World War II, the Uranium Committee sponsored an intensive research project on plutonium. The program was accelerated in 1942, as the United States government became concerned that scientists in Nazi Germany were developing a nuclear weapons program. The Army Corps of Engineers placed the newly formed Manhattan Project under the command of General Leslie R. Groves, charging him with the construction of industrial-size plants for manufacturing plutonium and uranium. The ideal site was described by these criteria:

- A large and remote tract of land

- A “hazardous manufacturing area” of at least 12 by 16 miles

- Space for laboratory facilities at least 8 miles from the nearest reactor

- No towns of more than 1,000 people closer than 20 miles

- No main highway, railway, or employee village closer than 10 miles

- A clean and abundant water supply

- A large electric power supply

In December 1942 it was reported that Hanford was “ideal in virtually all respects,” except for the farming towns of White Bluffs and Hanford. The federal government quickly acquired the land under its eminent domain authority and relocated some 1,500 residents of Hanford, White Bluffs, and nearby settlements, as well as the Wanapum people, Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and the Nez Perce Tribe.

The B Reactor was the first large-scale plutonium production reactor in the world. Construction began in August 1943 and was completed September 1944. By April 1945, shipments of plutonium were headed to Los Alamos every five days, and Hanford soon provided enough material for the bombs tested at Trinity and dropped over Nagasaki. Throughout this period, the Manhattan Project maintained a top secret classification. Until news arrived of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, fewer than one percent of Hanford’s workers knew they were working on a nuclear weapons project (in 1945, 44,900 people were employeed).

By 1963, the Hanford Site was home to nine nuclear reactors along the Columbia River, five reprocessing plants on the central plateau, and more than 900 support buildings and radiological laboratories around the site. Hanford was at its peak production from 1956 to 1965. Over the entire 40 years of operations, the site produced about 63 short tons of plutonium, supplying the majority of the 60,000 weapons in the U.S. arsenal.

Most of the reactors were shut down between 1964 and 1971, with an average individual life span of 22 years. The last reactor, N Reactor, continued to operate as a dual-purpose reactor, being both a power reactor used to feed the civilian electrical grid via the Washington Public Power Supply System and a plutonium production reactor for nuclear weapons. N Reactor operated until 1987. Since then, most of the Hanford reactors have been entombed (“cocooned”) to allow the radioactive materials to decay, and the surrounding structures have been removed and buried.